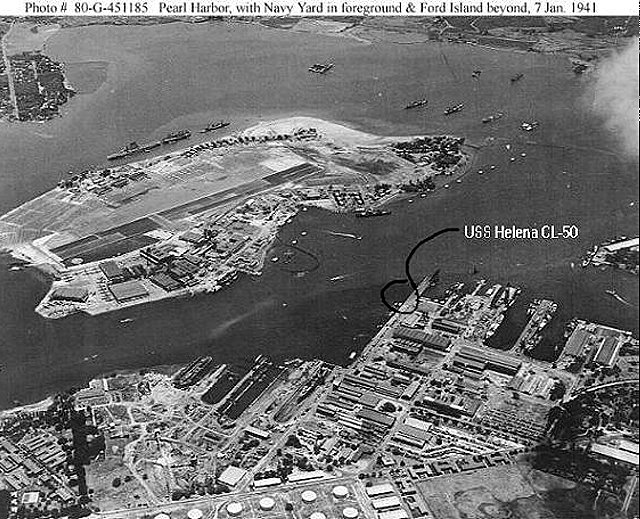

USS Helena CL-50

We also had a lot of darken ships when we were out to sea. The tension was mounting and everyone knew that we could expect to get into war at any time. Honolulu was crowded with service men, Army, Navy, and Marines. One week before the Pearl Harbor attack I wrote a letter home, saying I expect war at any time. Our mail was not censored at that time. Once the war started, you couldn’t say very much. “Everything going well, everything good.” Send your love and all that, but every letter you had to go through an officer. They checked everything, you couldn’t send any information. That’s why I say I got love letters. I got a whole pack of them that my wife kept. They all said the same thing. Anyway, the ship was getting ready for “Admiral’s Inspection,” that’s when the whole ship goes through a rigid inspection, even the double bottoms on the ship are open up and painted; a bad situation to be in before any attack.

On the morning of December 7, 1941, we were tied up to the Ten-Ten Dock.4

I had the 4 to 8 morning watch, called the auxiliary watch, in the after engine room. We didn’t have much to do on the watch, just make sure that the main feed water tank was kept full. The main feed tank was the boiler room’s feed water for the boiler that was steaming for ship’s use. We usually had night rations to eat, a chunk of bologna and a loaf of bread. We brought our own coffee, usually. I was relieved at 07:45 Sunday morning. I didn’t care to eat breakfast, so I told the mess attendant to clean up. I intended to go ashore on liberty and get a chocolate milk shake and a hamburger at the YMCA in Honolulu, and also take a swim at the YMCA pool. Our ship was getting ready to hold Mass on the forecastle.

I took my towel and clean underwear into the wash room about 7:50 am. I got into the shower and had myself pretty well soaped down when the loud speaker came on and the Officer of the Deck started yelling “All hands man your battle stations, Japanese planes are attacking Ford Island. Break out service ammunition. This is not a drill!” A few seconds later, the whole ship shook and there was a heavy explosion and fire. Our ship had been hit by a torpedo launched from a Japanese torpedo plane. The torpedo passed under the Oglala and hit us in the forward engine room. The blast was so powerful that Oglala rolled over on her side. I felt a hot blast of air go by me and then out the two port holes which were open. Thick, black smoke filled the room. Luckily, I was not burned by the blast, but I was choking from the acrid smoke. I fumbled to find my underwear and shoes. I put them on and made my way up to the next deck where I ound it easier to breathe. About 30 seconds later I went down the ladder and tried to get to my repair station on the lower deck. The smoke was still heavy on the lower decks so I stayed with the men until the lower decks cleared out.

By then there were men walking around, screaming, crying and moaning from the painful burns that they got from the flash of the torpedo. Their skin was peeling away from their bones, it was a really horrible sight. They were screaming for someone to help them, but most of us were in shock ourselves and didn’t know what to do for them. We only had a few hospital corpsmen and they were giving morphine shots to as many men as they could find. If their moaning continued, they got another shot. One of the corpsmen later told me that he knew that some of the men got enough morphine to kill them, but those wounded were burned so badly that they were going to die anyway. It was an act of mercy to put them out of their pain. A friend of mine named Robert Arnesen had been washing clothes about six feet from me in the washroom. He was burned by the fireball and died about two hours later with third degree burns over ninety percent of his body. What a terrible and painful death those poor guys went through. We could do nothing but feel sorry for our shipmates. There were many burns on legs which wouldn’t have happened if we were not wearing short pants. The short pants were fashionable in the British Royal Navy, and we had adopted a similar uniform to make us more comfortable in the tropical climate. We made every effort to get our wounded off the ship and over to the hospital. There was a shortage of ambulances, so we used a flatbed truck. Our guys returning from the hospital detail told us that there were so many wounded men coming to the hospital that they had to leave our wounded outside on the lawn.

Our power had been knocked out when the torpedo hit the forward engine room and forward fire room. However, we had large diesel generators, forward and aft, and they started to furnish lights and power to the antiaircraft guns, within 2 or 3 minutes. To add to the confusion, our 5” aircraft guns were firing at the Jap planes. Our chief engineer arrived on the scene. He was Lt Cmdr. Charles O. Cook and started to give orders after establishing communications with the bridge and fire room that was trying to raise steam on the after boilers. They were having a hard time trying to make the cold oil burn with natural draft. They were making a lot of smoke, which in a way helped to hide a bunch of ships from the enemy’s sight. Chief Engineer Cook got word that the aft boiler room was getting water in the bilges from the flooded engine room up forward, so he ordered me to take a submersible pump to the fire room. While carrying the heavy submersible pump to the lower level fire room, I had to walk over 4 dead bodies, lying in the passageway just outside the forward engine room. Their bodies were burned black and I could only recognize one of them. It was such a sickening sight that I wanted to vomit, but there wasn’t time. It will be a memory that I will keep the rest of my life. I wake up in the morning after 61 years and it flashes back to me. I was about to enter the hatch to the after boiler room, carrying that pump, when there was a loud explosion about ten feet from me on the outside of the ship. A 500-pound bomb had exploded on the outside of the ship making a large dent in the steel bulkhead, we discovered later on during inspection of the ship. I was hit on the left side of my face with heavy chips of paint from the outside bulkhead of the ship. It hurt a lot and I thought half of my face was all cut up. To my relief it turned out to be only a few scratches. I thanked the Lord for saving my life a second time that day. Then, after all I went through to get there, I was told that they wouldn’t need the submersible pump, that they were making some steam and using the bilge pump to take out the seeping water leak. I was still running around in my shorts and shoes, but I was able to find clothes from someone. About 10 am a second wave of planes came at us and the ships in the harbor, but we were ready for them and put up a heavy stream of fire with our 8 five-inch antiaircraft guns and they veered away from us and dropped their bombs on other targets. However, they dropped 4 large bombs close to the starboard side, narrowly missing us. One of the bombs was the explosion that stung my face with chipped paint from the bulkhead wall.

After this bombing run, I snuck up to topside to see what the score was.

About 8 pm on December 7th, our carriers which were out to sea at the time of the bombing sent in some F4F Wildcat carrier planes to Pearl Harbor for our protection. The ships in the Harbor had no word that they were coming and they opened up on the planes. The Helena did the same and some ship shot down 2 of our own planes. Tragically, three pilots were killed, including one who was hanging in his parachute. It was a bad mistake but the harbor had no real communications with the other ships at sea. It seemed everyone was trigger happy and wanted to kill something or someone. I later heard stories about Marines in town that would shoot anybody that looked suspicious on the street. I was put in charge of a detail that had to dump the garbage on the dock that night. I made sure the Marines were notified 2 or 3 times before leaving the ship.

After the Attack5-----5a

My first thought was to let my family know that I was okay. I sent them both a telegram and a letter, just to make sure. The communications out of Hawaii were so jammed up after the attack that the letter actually arrived first. December 7 is important for another reason, it is Alma’s birthday.

After our ship was informed that the planes were friendly, our own, we all settled down and decided to drink coffee, smoke cigarettes and talk the rest of the night. I wandered over to the bulletin board to just see what the movie was going to be for Sunday night. The title seemed to fit in to what had happened. It was “Hold Back the Dawn.”

Then I looked for my good buddy, Eddie Bartlett, 6

who worked with me in the machine shop. I found out from John Moss, another machinist mate 1st class that he and the master at arms in our “A” division, named Cornbloom, had taken him to the base hospital. They said he was burnt real badly and they didn’t think he would live. I found out a couple of days later that he was still alive. So I visited him. I almost broke down when I found him lying on sheets of wax paper. He said he wished he could die; he was in terrible pain. I brought him a coca cola and a straw and hand-held it while he drank it. That seemed to give him a little encouragement while I kept telling him that we had to get back at the Japanese for this treacherous deed. I tried to get off every afternoon while we were there and feed him more cokes. He later admitted that this helped him to keep living. Eddie stayed in the Navy, and got transferred to Washington D.C. after healing up. He quickly advanced from machinist mate 2nd class to Ensign, a commissioned officer. He retired as a Lt. Cmdr., U.S. Navy, and was the executive officer in the Philippines when he retired. We got together 3 times with him and his family, wife Marie and son David. Our last meeting was at his sister’s house in Florida. Ed and Marie had bought an $80,000 motor home and were touring the country. However, the burns he got in Pearl Harbor seemed to affect his nervous system and he died a few years later, I think he was about 70 years old.

Getting back to the days that followed December 7th, all hands got back to ship routine, cleaning up the ship and repairing what we could. We started right away to pump out flooded compartments and to clear out debris and ruined machinery from the ship’s forward engine room and nearby compartments. The ship’s galley was in bad shape with smoke damage and had to be cleaned up. Within two days, a couple of tugs pushed the ship into a dry dock 7

and the yard workers started repairs on the hole in its side. We knew that we were heading back to the states as soon as the Navy Yard workmen could put a false bottom on the part of the ship that was damaged. We were in dry dock so I got a good look at the damage that one torpedo can do. I estimate we had a hole on the starboard side about 40 feet long and 12 feet high. I never saw yard workmen put so much effort in their job. We had a few false alerts while in dry dock and those workmen really ran to get off the ship each time.

We left Pearl Harbor for the states on our own power, with two turbine engines and 4 boilers that were still operable. We could make about 15 knots at top speed. Two of the dead screws were removed from their shafts so that there would be less drag for the 2 remaining engines. We brought the screws back to the states with us on the deck of the ship. The ship was in Mare Island Navy Yard for at least six months getting repaired.

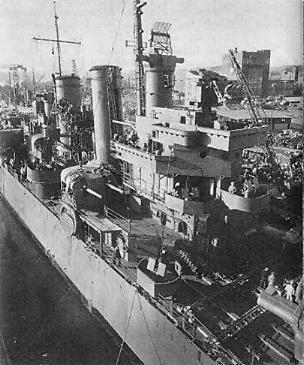

View of the starboard side amidships, taken at the Mare Island Navy Yard, California, 27 June 1942, following repair of combat damage and an overhaul. Note the ship's

redesigned forward superstructure,

including an open bridge and reduced

lower bridge wings. Mark 34 main battery

gun director, with antenna for an FC gunfire

control radar, is immediately in front of the

foremast. The other director, just behind the

open bridge, is a Mark 33, with antenna for

an FD radar mounted on its front. Weight

traversing gear on the main deck, between

the forward superstructure and 6"/47 gun

turret # 3, indicates that Helena is

undergoing an inclining experiment to

determine her stability.

Photograph from the Bureau of Ships

Collection in the U.S. National Archives #19-N-31213.

All hands got at least 30 days leave while in California and I flew home to see my girlfriend Alma and all of my family. Time went by real fast, visiting all my friends. Alma said she would wait for me when my leave was up. My Mom and Pop hated to see me go back and Mom even asked me what would happen if I didn’t go back. I remember saying “they would just shoot me.”

Air view of Pearl Harbor's 1010 dock.

This was a spot normally reserved for the battleship USS Pennsylvania, flagship of the fleet.

The Pennsylvania was in dry dock. Because we were at the Pennsylvania’s spot, we received extra attention from the Japanese torpedo planes and dive bombers during the attack. They thought we were the flagship. A map was recovered from one of the Japanese planes shot down that day; it had a big, red arrow pointing to the spot where the Helena was docked. The old mine layer, USS Oglala was tied up on our starboard side.

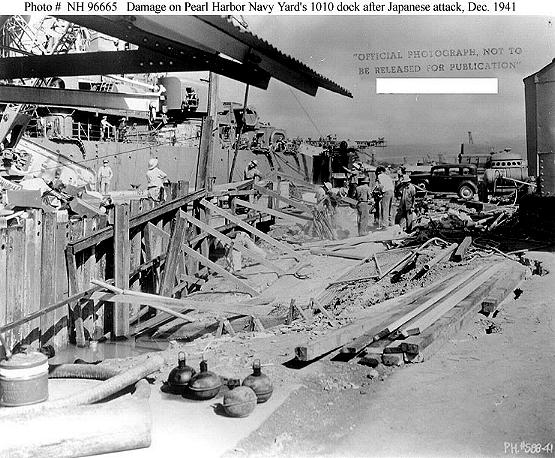

Bomb Damage to the Navy Yard Pearl Harbor 1010 Dock. December 1941.

That's the USS Helena CL 50 on the left.

The USS Helena CL-50 at the 1010 dock in Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941. Cassin and Downers are burning in drydock, ahead, with the Pennsylvania.

Helena has a torpedo hole in her starboard engine room and Oglala is lying on her side in the foreground. An aerial torpedo went under USS Oglala and hit the Helena.

Oglala, which had been tied up alongside the Helena, was towed clear before capsizing.

Picture provided by LTJG Bin Cochran. USS Helena CL-50.1942 - 1943.

I was amazed to see so many burning ships. The Arizona was burning badly. The Oklahoma was lying on its starboard side with almost half of it above water. The Nevada was beached. What a sickening and demoralizing sight to behold. It was only a quick look but I was thankful that our ship was in better shape than the Arizona or the Oklahoma. The Japanese made a third run about 11:30 am but they stayed up high and their bombs missed most of their targets. They must have been taking pictures of our smoking harbor and laughing over their feat of treachery. We spent the rest of the day, December 7, 1941, cleaning up the ship and getting the dead and wounded off the ship. Most of us didn’t get anything to eat until that night; the cooks were able to make up some sandwiches and hot coffee. We also had to eat sandwiches for most of 3 days until the galleys were clean enough to serve food.

They put on more antiaircraft guns, 4-barrel, 40 millimeter antiaircraft guns that were made in Sweden. They could really eat up the ammunition when they were firing at a plane. We also got the latest radar system installed, which proved itself later on.

4Plan of the Day. 7 December 1941 5Pearl Harbor Damage 5aPearl Harbor Damage #2 6Casualty List 7Dry Dock